The Bridge over the River Kwai.

One soldier’s incredible story, I intended to publish a post on the bridge over the River Kwai, however I changed my mind and decided instead to tell a soldiers incredible story. That soldier is my late uncle Allan Herd, the toughest bravest man I ever knew. Sadly Allan passed away aged 95 on July 8th 2012, after all he had endured in his life we all knew he wouldn’t last too long after losing Marie, his loving wife in September 2011.

Allan Herd 1940.

One soldier’s incredible story

Members of my family experienced the horrors of war, Dad was in Darwin when it was bombed, Uncle Nug (Arthur Tippett) was on the Kokoda trail, Pop Tippett (Samuel John Tippett) was at Gallipoli, and among other things was blind for three months from the effects of mustard gas. Consequently growing up in such a family gave me a great appreciation of the huge sacrifices and tragedies these wars bestowed upon the people in our country.

However no story I have ever heard comes close to the one I want to now make you aware of. Allan Herd was a rat of Tobruk fighting in Syria and Lebanon before making a last minute escape at Suez, he vividly remembers seeing all their baggage and equipment left abandoned on the dock as they fled on board a troop ship and headed for the Philippines.

He remembers cheating death many times, starting in the middle east when travelling in a convoy of trucks enemy machine gunners fired over their heads for some unknown reason instead of firing straight at them at point blank range. He also spent three days buried in sand in a shallow trench while a fierce sandstorm raged over and around him.

They left Suez for Colombo and then headed for Java where they were put ashore in with only one weapon to each 3 men or so. All their kit and weapons had been loaded onto another ship in Suez and eventually arrived back in Australia. “Black Force” as it was known, named after the CO Brigadier Arthur Blackburn VC, fought for about 3 weeks before they surrendered to the Japanese. They were held in Jakarta before being shipped to Changi.

Allan was one of 1200 troops who were transported on what he describes as “the ship from hell” which was actually bombed by American Liberators, setting the ship on fire, the guys who ended up overboard remember the sea being alive with snakes.

Allan is very critical of our Generals inability to make sound decisions before they were captured while the ship was docked in Java. Most of the time he spent in the sick bay suffering from Malaria.

The next stop in his incredible saga is a couple of years working on the Burma railway, and some of his classic comments will stick with me forever, Allan said;

“Those Pommies had no stamina, they started dying within a week”

He also said; “The guards were Korean, they were the worst torturers in the world, and the biggest cowards.” “After one bashing from a Korean guard he put his rifle to my head and started to pull the trigger, I didn’t react because by that time I had no fear of death”

When I asked Allan about the food he said “the food was ok, moldy rice and meat, the only problem was the meat came in the form of maggots.”

He tells how they were given a daily quota of so many meters of track to be laid, the teams started at around 50 prisoners, however as they died or were killed by the guards the quotas were never reduced, they simply had to stay on the job longer.

Allan told me “by now you are in a zone and you act just like a robot”, perhaps that explains why he had no fear of death however his words may well describe it differently.

The Japanese then chose the fittest 500 prisoners to be transported to Japan to work the mines, and naturally Allan was one of those picked. As Singapore was under blockade they squeezed them into rail cars and sent them to Saigon in 40 degree + heat, they were packed so tightly that anyone who collapsed still remained upright. Upon arriving at Saigon they found that port under siege as well so they were turned around and sent back to Singapore where they were eventually put on a ship for Japan.

His home for the next year or two he calls “the camp of the sadists,” can you imagine what he endured there? He remembers working the mines in the middle of winter without any clothes. I once again asked about the food and he said there was no more rice on the menu only millet, a couple of times a day seven days a week. For those who are not familiar with millet, it is basically birdseed.

My question is how much can any man tolerate? As far as I’m concerned my Uncle is the toughest man I have ever known and ever will know. What do you think?

Finally the guards abandoned the camp leaving them with no food etc. they had no way of knowing Hiroshima had been bombed, then three days later they were spotted by an American aircraft, rescued and sent by train to Nagasaki where they saw the smoking ruins of the city before being put on another ship bound for the Philippines.

I keep getting flashbacks as I am writing, Allan was the second eldest of a large family, 4 girls & 3 boys raised in Norval St Auburn in Sydney Australia, and during the great depression he scored a job somewhere in the city where he worked for almost nothing, consequently he did not have the funds to pay for the train so he simply ran the 15 miles to and from work, rain hail or shine.

Any mistakes in the above story about Allan’s experiences are mine, however I am so glad I had the pleasure of him personally relating to me his incredible tale. My note taking leaves a bit to be desired so I may have certain facts out of sequence. When you read his story you will understand the meaning behind his poignant poem;

For when the Gates of Heaven I reach,

To Saint Peter I will tell;

A survivor of Blackforce reporting sir,

For I have served my time in hell.

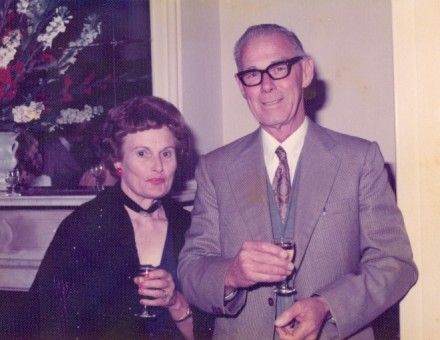

Allan & his wife Marie in 1982, when he wrote his incredible soldier’s story.

It is Christmas of 1982 and I cannot help but look back to a Christmas of 1944 when a party of about 500 men were about to be taken on a journey inside the gates of Hell and those that survived would be blessed with a second life, a miracle from Almighty God that is granted to so very few.

Among those to receive such a blessing was George Scott of the 2/6th Field Coy. Royal Australian Engineers of the 7th Division.

Fate was to throw George and myself together for over five years, one always in the shadow of the other, for where I was, so was he.

My name is Allan Herd. My regimental No. was NX 25438. My Japanese P.O.W. No. was 1444 (Sen Yon Harku Yon Ju Yon).

It was my great fortune to be a member of the 2/6th Field Coy. Royal Australian Engineers of the 7th Division, a wonderful trained company of men, who were sincere and honest in their aim to carry out their duty to the full limit of their ability and endurance for their country in its hour of need.

It was at Ingleburn, when the Company was being formed, that I first met George, a tall, lithe and very brown skinned young recruit, who hailed from a suburb of Sydney abounded by beaches, so one could – using 1982 slang say that George was a surfie – a good sportsman and a man who loved life.

On fulfilment of its training, the 2/6th Field Coy. Embarked on the liner, Queen Mary, in October, 1940 and sailed under convoy with the other super liners, the Mauritania and Aquitania.

We disembarked at Bombay in India, where we went into camp on the outskirts of the city, while preparations were being made to form another convoy, for at that time, the huge liners we travelled on were considered to be at too much risk to proceed closer to the Suez Canal.

On the formation of the convey, we embarked on the Dutch ship, Slamat and reached the Suez Canal without incident.

We disembarked at Port Tewfick, then travelled overland to Quastina in Palestine, which camp was the Engineers training camp for the A.I.F.

After several months of training at Quastina and the bridging school at Haifa, the Company with C.R.E. Headquarters, moved out over the Siniai Desert to the canal, thence crossed into Egypt. From there, we tailed the 6th Division in the big drive into Libya, the Company now being under British command as corp engineers to the British Army.

Two of our men won the George cross in Tobruk for heroism in saving an ammunition ship.

We mined the nerve spots of the town of Bengazzi and just got out before the Germans attacked. We by-passed Tobruk and reached Mersa Matruh, being very fortunate to miss any air attacks on the way and Tobruk was surrounded the next day, so we were fortunate we were not caught in the long siege. We were then put on orders to sail for Greece, but this was cancelled only hours before we were to leave.

Then tragedy struck the Company when a mine field blew up while the men were laying the mines in rows, one accidentally exploded and the rocky nature of the terrain and the highly sensitive anti-personnel mines, the whole field went up and the Company suffered bad casualties.

We left the desert after some months and rejoined the 7th Division and moved up to the Syrian border in preparation to invade both Syria and Lebanon, which, being under Vichy French, posed a threat to the British army in Palestine and the Suez Canal.

Again the Company fought hard and well and at a successful conclusion some weeks later, had won more than its share of bottle honours, though it suffered heavy in casualties, losing some of its best men.

After being snowed in in the mountains of Lebanon for Christmas of 1941, we were ordered back to Quastina in Palestine and our places were taken by 9th Division Engineers.

We were told we were chosen for a job and moved out over the Siniai Desert, back to the Canal and embarked on the Orcades, which left in such a hurry that our arms and gear were left behind with our baggage party. The ship ran unescorted on her own and reached Colombo at dusk one evening, with the news that Singapore had fallen to the advancing Japanese.

We left in the small hours of the morning and rendezvoused with a Dutch destroyer which escorted us to the port of Oosthaven in Sumatra, where we went ashore, poorly armed with ship carbines – one to one man in five, with a few rounds of ammunition. Our job was to destroy the oil wells, but we were too late, as the Japanese had landed and were already in control of the wells. We went back on board the Orcades and sailed to Tilijap, the port of Batavia in Java.

We were ordered ashore by General Wavell, though there was a lot of hostility by the Dutch, who did not want to fight, as they wished to declare their cities open and thought the Japanese would just let them carry on as usual under Japanese administration as in French Indo China.

We landed as Black Force, being under Command of Brigadier Blackburn V.C. of the 2/3rd Machine Gun battalion – without a machine gun – and the 2/2nd Pioneers, plus a small transport and medical group – all told approximately 2,500 men.

We were the bait – the sacrifice to mislead the Japanese into thinking that the 6th and 7th Divisions had landed – and to this small force fell the glory of standing on the Field of Honour – the last thin line of defence before Australian territory.

After a period of small, sharp clashes with the oncoming Japanese, we were ordered to withdraw and retreated to the other side of the Island. Under pressure from both the Dutch and Japanese, the force was forced to surrender, which was done with great bitterness, for after destroying our arms and ammunition, the men were rounded up and put in a Dutch jail. Nobody, except those that have experienced the terrible shame and disgrace and shock that comes to a proud Company of fighting men that are forced to surrender when they have been prepared to fight to the end, will ever know the trauma and gut wrench it is to a soldier, who will never forget for the rest of his days. To be betrayed and abandoned by their country as the men of the Black Force were, will be a black mark on Australia and her people forever – no matter how much they hide and keep quiet about Java, the truth will come out.

VIA DELOROSA

After about four months in Bicycle Camp (a Dutch barracks) in Batavia, we were put on a hell Ship and taken to Singapore and linked up with the 8th Division and British Forces, who were in the Changi area.

After a while, the Japanese took about 2,000 of us, being 1,000 Australian and Americans from Java and 1,000 Dutch and Indonesian army personnel, to the port of Penang in Malaya and there we embarked on two Hell Ships, escorted by an armed minesweeper and set sail for Moulamein, a sea port in Burma.

While in the Bay of Bengal, the ships were attacked by two Liberator bombers, operating from India. The Dutch prisoners’ ship was sunk immediately and our ship was on fire from near misses, but we survived as the planes ran out of bombs and ammunition and turned back to their base.

Australian Sailors (survivors of H.M.A.S. Perth) and American sailors (U.S.S. Houston) put out the fires, but there was no way of escaping with the ship to India. Casualties were pretty light among the prisoners, considering the circumstances, but the Japanese were very hostile towards us and refused any medical help to the wounded, some of whom died from gangrene as a result.

We landed in Moulamein and were promptly put in a native jail and after several days, we marched out to Kilo 18 to begin our first leg of the Burma Railroad of Death, where we were to toil and die through virgin jungle for nearly two years, until we linked up with the parties working from the Thailand (Siam) end.

We slaved and died from Kilo 17 to 55 to 75 to 105 Kilo and the jungle cemeteries were littered with hundreds of white crosses, that even the Japanese Officers and commanders became alarmed and sent sick men to die in other places so the cemeteries would not be so big, for they must have felt the noose around their necks should they lose the war. Through two wet seasons when cholera wiped out all native slave labour and a large number of prisoners – our immunization saved us from a terrible death and the Japanese and Korean guards lived in terror of this disease, for they feared it more than anything else.

During the wet season, in which it rains for over three months non stop, with an average fall of 400 inches, we worked and starved under atrocious conditions, everything rotted, including the human body and Mother Nature added to our misery with sand flies and every other affliction of disease and pain and torment that one could ever devise.

After completion of the line, the Japanese took survivors to a camp at Tamarkham in Thailand, where they had promised us good food and rest to bring us back to health again and to treat us better, for the survivors of the line had reached the Gates of Hell – conditions such that it was almost impossible for the human body to survive.

Such for Japanese promises, for after a few short weeks, they took about 1,000 of what was considered the fittest men and under a Brigadier Varley of the 8th Division, they set out to try and get us to Japan.

They put us in cattle trucks, jammed in tight like sardines in a tin and set off on a nightmare journey to Saigon in Indo-China, for at that time, American submarines had Singapore harbour bottled up. We travelled for some days, till we reached the Mekong River, where we embarked on a ship and travelled to Phnom Phen in Cambodia, thence to Saigon. After spending several months in Saigon, working on the docks and aerodromes, the Japanese started to take us back again as they could not get across from Saigon to Japan because of Allied submarines.

So we commenced the long arduous journey back, but this time it went right through to Singapore, where we were put in a Ghurkha camp in River Valley Road. We were split up into kumi of approximately 200 men each – our kumi being No. 40. After about a month, the Japanese embarked about 2,000 English and Australian under Brigadier Varley and set off for Japan.

They never reached their destination, being torpedoed by American submarine Barb – Queenfish – Pampanito – Sealion and less than 300 were to survive.

The full account of this hell at seas can be read in the book “Return from the River Kwai” and every man, woman and child in this country should read this book and learn to think and to thank God that there were born men like these.

We knew back in Singapore that the ships had been sunk, but did not know of any survivors and the 2/6th Field Company had about 11 of its men aboard the ships and only one survived, he being washed up miraculously on the China Coast.

After about four months or so, working around Singapore docks and aerodrome, we kumi 40 began to think that we would not be going to Japan, but just on Christmas of 1944, we were ordered to embark and so began our journey through the gates of hell itself.

We went aboard a fairly modern Japanese passenger-cargo ship on a hot day and were immediately all crammed into a steel hold with only one door entrance which was locked behind us.

In terrible temperatures, crammed shoulder to shoulder so as when men passed out, they could not fall, the Japanese kept us there for what seemed hours and when they opened the door to pass the unconscious men out, they told us that this was a warning to behave ourselves on the journey. There must have been 2” of perspiration on the floor of that hold and the stench became unbearable as the day wore on.

The convoy of ships ran under guard of what would have been the last of Japan’s mighty navy and maritime fleet – being just a handful of ships. We were lucky, for the Americans had withdrawn their submarines for the attack on the Philippines and though we hugged the China coast for safety.

As the ships neared the Japanese southern most island of Kyushu, the weather had been getting colder and colder till we reached the port of Mogi in blinding snow. After being in tropical and hot countries for nearly five years and with no body fat or clothes, we now faced the terrible fate of freezing to death and that is when nature did what the Japanese could not do – she commenced to break the spirit and determination of the men to survive – for when you freeze day after day, that is when you wish for death.

We were taken by train at night, overland to the coal mining town of Ometu in Fukuoka Prefecture. There we were put in fairly good barracks and issued with some clothing and a blanket, but it was freezing cold with three or four inches of ice under foot and sleet ice blowing over the ocean cliff into the camp for 24 hours a day, week in and week out. God had forgotten this place on earth, for just to see it was to know death. There was no grass, no birds, just nothing, as there were zinc works nearby and everything had been killed by the fumes from these works.

The camp was built on the cliff edge with electric wires and sentry boxes all round and the sleet and ice drove in from the ocean and for sheer desolation and isolation, this camp must have been Satan’s own.

The camp Commander and N.C.O.’s were Japanese and the guards also and they would have been the most cruel and sadistic you could ever find, for they revelled in torture and death was metered out for the most trivial things, that the average person in Australia cannot comprehend and does not believe.

After the Japanese, the camp was controlled by the Americans who had been there for some time, being survivors of the Philippines campaign at Bataan and Corrigidor. Outside of a small minority, the bulk of them were the lowest form of white men you could find – treacherous racketeers, no mates as we know mates and I found that the Americans cannot take adversity and become like animals in their bid to survive. The camp was full of them with one arm or one leg missing and it appears, to get out of the coal mines, they would put their arms or legs under the coal skiffs or trucks and risk the survival shock, but in the weakened conditions of the men, many must have died taking the chance.

We were given a weeks training in the bitter cold on some coal heaps and then graded into our working party of which George and I drew the Jackpot – the hardest of all Saitan – the work of a fully fledged miner – to work the coal faces both large and small in broken shifts of approximately 12 hours each shift. Every man had a quota of trucks to fill before he could finish and with the help of his Joe (Guard) it usually took about 12 hours – the last two being when he would be belting and driving you to finish in time.

The mine was about one kilometre from the camp and when counted and checked out from the Guard House, you would march to the mine, be taken to a room where you changed into a G-string or shorts – a miner’s lamp with a battery nestling down the small of the back and cap with lamp being your working outfit. Then you would be allotted to your Joe and you might be on a large face of 20 to 30 men or a small face of 4 to 6 men.

He would take you across the ice to a large building where, on entering, you would see a huge idol of a miner. There your Joe would bow and pray and you had to follow what he did as he prayed for safety and to return out of hell each shift. It was the biggest and oldest coal mine in Japan and ran for miles under the ocean bed and death would reap a bountiful harvest there amongst Koreans, Japanese and prisoners.

This mine was to collapse in the late 1950’s with great loss of life, but it was no shock to us, as we expected it to go any time when we were underground.

I will not tell of the horrible torture, of death and sadism practised by the guards and the Jap Commandant, for this is told in books such as “Slaves of the Sun of Heaven”.

Our food was mainly millet, which was like gravel, and passed through your body within hours of eating and hunger was worse than ever, as the work and freezing cold made terrible demands on our bodies. Men’s lungs collapsed from the terrible cold and they died in agony for there was nothing one could do. By now a terrible change had come over the men. There were no more jokes or horse play, which is part and parcel of an Australian. No more laughter for under the 24 hour shifts, men were divided and as we came stumbling back from the mines, a new shift was leaving, so you never saw or spoke to any other party except the men in your own group and after a while, you did not even speak, only snarled for the terrible cold and starvation and work had now broken us down and we knew we were doomed and death would be a welcome release.

The weeks dragged on slowly and the work seemed to get harder in the mines, and one day in the mines was equal to 10 days work on the Burma Railway, but they continued to drive us harder as they wanted greater effort for their war effort.

Then suddenly a change started slowly to appear in the form of planes and air raid warnings and we now got less sleep after returning from our shift, as the guards would go berserk whenever the air raid siren went and drive us down into the underground shelters which were cold and damp. One night, with a gale blowing over the cliffs from the ocean, the sirens went and after reaching the shelters, we could hear the planes as they passed overhead, followed by a swishing sound, but no explosion, and this went on for hours. Word came from those nearest the entrance that the planes were dropping incendiaries and when it was all over, we emerged to find about one quarter of the camp burnt out, but as expected, no damage to the mine.

In the next few days, the Japanese collected thousands of unexploded incendiaries, all over the country side and as we would go to work, we would pass huge stacks of them by the road.

I had been on light duties in the camp for about a week, as I was too sick to go down the mine and I knew my days were numbered, for I was living in another world, the twilight world where there was no hate, no fear of death, no wanting to come home, only a peace that is so complete it cannot be described.

Then they came, on a bright clear day – thousands of bombers and fighters that the sky was black with them and the ground and building shock as if in an earthquake and we did not get to the shelters, when the fighter escorts dived down over our heads so low, they skimmed the roof of the huts, but they spared us for they must have realised we were prisoners.

A few days later, no shifts went to the mines and all the Japanese would say was that it was a holiday, but it carried on and then we realised the war was over.

So terrible had been the suffering, so far gone were the men, so exhausted and spent, that when it was realised that the war was over, there was not one cheer – not any laughter – just nothing and if anybody said anything, he was snarled at and abused. It would be hard to comprehend that that could be a fact, but before God, I swear it is the truth.

The Japanese just disappeared about a week after the work stopped and left us to starve. We were found by American War Correspondents, who parachuted into the camp and with their radio in touch with Macarthur’s Headquarters, bombers were flown in with food to be dropped into the camp.

The Americans in the camp had now assumed full control and started to get things done in a more orderly fashion. After about four weeks, we were told that all Australians were to be moved out that night by train fro Nagasaki.

We boarded the train and after stopping and starting, all night long, we came into the valley of death, which was the site of the city of Nagasaki.

The atom bomb meant nothing to us, as we had not heard of or knew anything about it, but if the human race could only see the desolation and destruction as we had seen it, there would be no more wars.

The train crawled slowly through this holocaust – hour after hour – and the destruction was complete. No life, be it human, bird, insect, just nothing.

The only thing that was left was a wharf on the bay and here the train pulled in to several brass bands playing and American men and women in uniform, cheering and whistling. They passed us coffee and donuts through the windows of the carriages, but kept well back and did not touch us or shake our hands.

They had been instructed not to show any feeling or say anything, for we were not human to look at, being more animal and being lousy with lice and coal dust ground into our shaven scalps and our eyes and our staved bodies in rags.

After being de-loused through the showers on the wharf, with plenty of detergents thrown over us – all we possessed was destroyed, except personal photographs if any, and we then passed through a double line of doctors – then issued with pyjamas and ships slippers and put aboard the American Hospital Ship U.S.S. HAVEN, a name so appropriate, after all the suffering, that God had granted us survivors a second life.

The survivors of the 2/6th Field Company – George and his mates – never betrayed or lost their loyalty and love for their country.

I wonder how much can be said for the people of this country today, who have betrayed these men with their greed and selfishness, whose God is the “Car” and “Money” and “I’m all right Jack” attitude, who have never known or tried to understand the suffering and problems of the men who came back from the dead.

Not all people are in this category, but they are in the minority, for the knocker, the shrewd and the power hungry reign supreme and the lie has taken over from the truth and Christian morals have been thrown out of the door.

To us that returned, comes the question – was it worth it?

I let the people of Australia supply the answer, for they have to answer the Judgement.

ALLAN HERD – NX25438

Sen Yon Harku Yon Ju Yon

For when the Gates of Heaven I reach,

To Saint Peter I will tell;

A survivor of Blackforce reporting sir,

For I have served my time in hell.

After about a week aboard the hospital ship U.S.S. HAVEN, in Nagasaki Harbour where she was moored as a base hospital, I decided to try and leave the ship, so I approached the Executive Officer with my request and was promptly refused on the grounds of my fitness and emaciated condition.

However I persevered with my request and eventually about 3 days later it was granted, providing I sign an agreement absolving them of any liability or blame.

I was outfitted in an American G.I. uniform and embarked aboard an auxiliary aircraft carrier and with about 30 other P.O.W.’s of various nationalities we set sail for Okinawa.

After about 4 days at sea we reached Okinawa about midday, on a beautiful clear and sunny day, and as far as the eye could see there was literally speaking thousands of ships of all sizes, from the largest of battleships to the smallest tugs all at anchor there.

We went ashore and were put in tents, being under the jurisdiction and care of the Red Cross, and were looked after until arrangements were made to fly us into Manila in the Philippines. At Okinawa there was still fighting going on among small pockets of Japanese who would not believe that Japan had surrendered.

About a week or so later my name was called out and I was on my way to Manila aboard a Dakota Transport plane of the U.S.A. Air Force and although I had been issued with 3 blankets for the flight, it was very cold and rough throughout the flight.

The Australian Staging Camp was large and well laid out, the tents were comfortable and everything was done by the Americans to make our stay as comfortable as could be. We were never allowed out of the camp, being guarded by American Troops, for in our mental and physical condition it was done for our own protection.

After several weeks the Australian reception group arrived to check on our Bon Fides etc, and then to put us back on strength with the A.I.F. and better still on the payroll.

It was here in the camp that all the trauma, stress and suffering that had been bottled up for years, came out in the form of the most terrible nightmares one could ever experience, and by the talk of our American guards next day they must have thought that war had broken out again.

After about 3 weeks or so, my turn to move on came again and this time I went aboard an R.A.A.F. Flying Boat, a Catalina, and after flying low over the ocean all day we arrived at the Australian held Morotai Island, and it was there that the canteen gave me my first time of Australian ready rubbed tobacco in over 3½ years, something I never ever expected to see again.

The next day we took off in the Catalina on our last leg to Australia. After flying most of the day we arrived in Darwin, and when I stepped on to the wharf the tears started to flow and I fell down and kissed the earth, for it was not the fear of death, for literally we had died many times, but the fear of being buried in a foreign land that haunted us most.

I was taken to Darwin Hospital and checked over the next day, then back to an Army camp and looked after, but never allowed out.

About a week later I was given 3 blankets and put aboard a Liberator Bomber, being domiciled in the bomb bay and we took off for Sydney, flying as low as possible, because at height we would freeze to death as there is no conditioning in the bomb bay for personnel.

Because of having to fly so low, it caused a serious accident, as an eagle flew into one of the engines, smashing it and the propeller, at that time we were over the Northern Territory 6, but continued on under the three remaining motors.

We reached Mascot Aerodrome around 6pm that night in very bad weather, but once we touched down on the ground nobody cared, for after five years overseas we were home.

God had been our pilot and brought us home and had granted us a second life, a blessing granted to so few.

In five years of war I had only two days and three night’s leave, that being in Alexandria (Egypt) where I was given leave from Mersa Matru in the desert.

ALLAN HERD

NX25438

1444 Sen Yon Harku Yon Ju Yon

Here is an interesting link about the Fukuoka POW camp.

Kanchanaburi cemetery on the River Kwai.

The Kanchanaburi War Cemetery (known locally as the Don-Rak War Cemetery) is the main Prisoner of War (POW) cemetery associated with victims of the Burma Railway. It is located on the main road (Saeng Chuto Road) through the town of Kanchanaburi, Thailand, adjacent to an older Chinese cemetery.

It was designed by Colin St Clair Oakes and is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. There are 6,982 former POWs buried there, mostly Australian, British and Dutch. It contains the remains of prisoners buried beside the south section of the railway from Bangkok to Nieke apart from those identified as Americans, whose remains were repatriated.

There are 1,896 Dutch war graves, the rest being from Britain and the Commonwealth. Two graves contain the ashes of 300 men who were cremated. The Kanchanaburi Memorial gives the names of 11 from India who are buried in Muslim cemeteries. Close by (across a side road) is the Thailand–Burma Railway Museum about the railway and the prisoners who built it.

15 May 1942

The Japanese began to move Australian prisoners of war to Thailand and the hell that would be the Burma-Thailand Railway on 15 May 1942. The first group, A Force, was 3,000-strong and commanded by Brigadier A. L. Varley. About 13,000 Australians were to be used as slave labour on the railway’s construction, with about 2,800 dying there and many more later passing away as a result of the inhuman working conditions. Overall, a staggering 61,811 British, Dutch, Australian and American POWs and 177,700 civilian slaves from Malaya, Burma, Java and Singapore were to lose their lives. May you all rest in peace.

The Japanese began to move Australian prisoners of war to Thailand and the hell that would be the Burma-Thailand Railway on 15 May 1942. The first group, A Force, was 3,000-strong and commanded by Brigadier A. L. Varley. About 13,000 Australians were to be used as slave labour on the railway’s construction, with about 2,800 dying there and many more later passing away as a result of the inhuman working conditions. Overall, a staggering 61,811 British, Dutch, Australian and American POWs and 177,700 civilian slaves from Malaya, Burma, Java and Singapore were to lose their lives. May you all rest in peace.

Prisoners huts.

Wonderfully preserved.

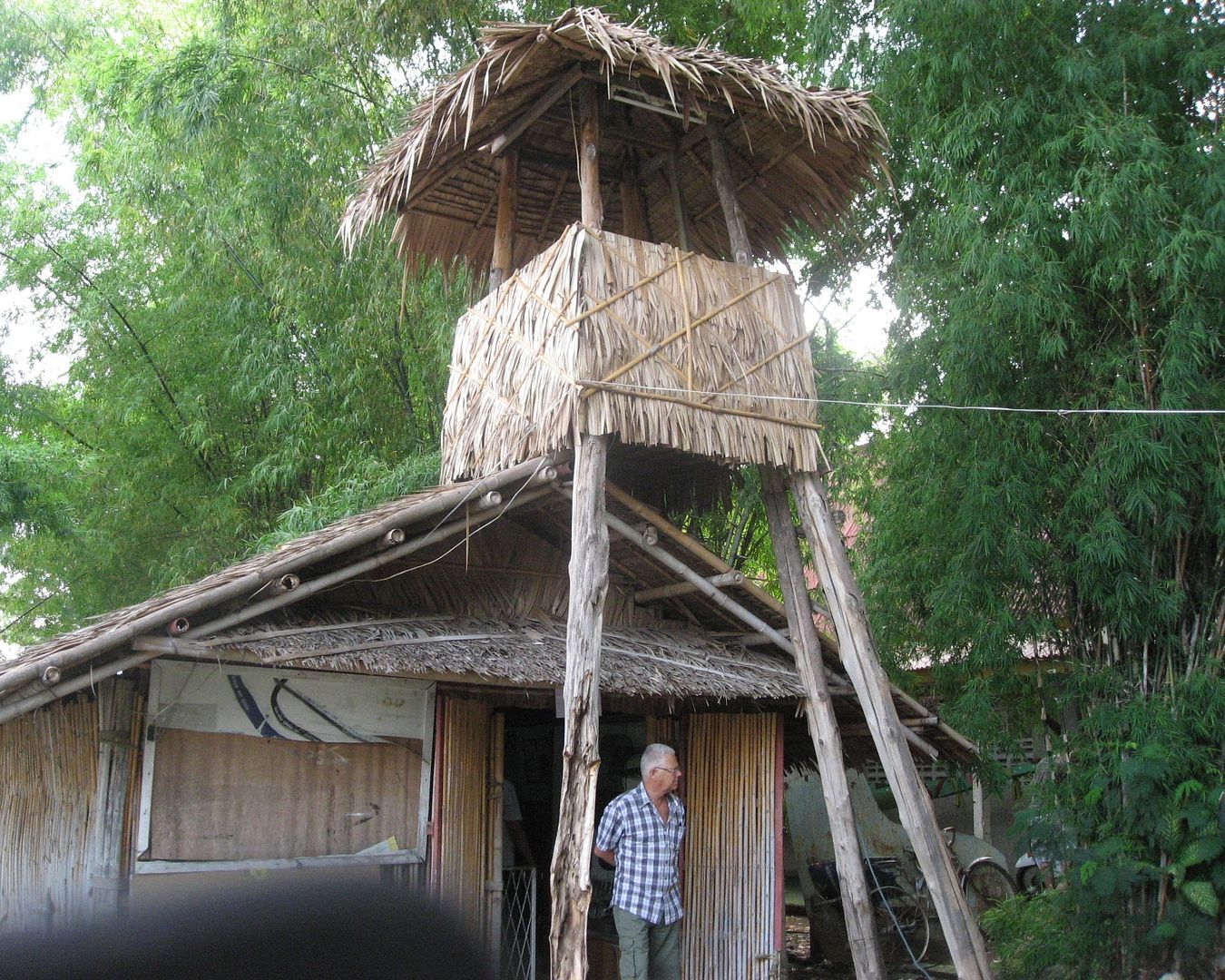

Guard tower.

My brother Warren coming out of the tower.

The famous bridge.

Rather unspectacular.

WW2 weapons.

Everyone one of them could kill.

Port Macquarie August 2010

I travelled to Port Macquarie with my brother Ian to visit Allan & Marie along with our brother Warren who also lived in Port. Our purpose was to present Allan with the Herd family history book that I had recently compiled.

I travelled to Port Macquarie with my brother Ian to visit Allan & Marie along with our brother Warren who also lived in Port. Our purpose was to present Allan with the Herd family history book that I had recently compiled.

Allan was a great story teller.

Allan was still sharp as a tack aged 93 and loved to tell us tales about his incredible WW2 experiences.

Allan was still sharp as a tack aged 93 and loved to tell us tales about his incredible WW2 experiences.

Warren and Auntie Marie

Sadly both Allan and Marie would pass away within the next 2 years. However knowing Allan he would have certainly mentioned how upon his return to Australia after the war that doctors told him it would be highly unlikely he would live past 60 because of what he had been subjected to. His classic sense of humour would have kicked in and I can guess he would have said “bloody doctors, what the hell would they know”. 🙂

Sadly both Allan and Marie would pass away within the next 2 years. However knowing Allan he would have certainly mentioned how upon his return to Australia after the war that doctors told him it would be highly unlikely he would live past 60 because of what he had been subjected to. His classic sense of humour would have kicked in and I can guess he would have said “bloody doctors, what the hell would they know”. 🙂

Warren, Allan and Ian.

Allan was always coming out with a humorous observation, he told us that a couple of days ago he took a fall climbing the front stairs to enter his home. Luckily he was not hurt, however he was quick to name the incident his “leap of death”. As I said previously, 93 years of age and sharp as a tack. I hope you have enjoyed this one soldiers incredible story, I would love to see it made into a book or a movie one day.

Allan was always coming out with a humorous observation, he told us that a couple of days ago he took a fall climbing the front stairs to enter his home. Luckily he was not hurt, however he was quick to name the incident his “leap of death”. As I said previously, 93 years of age and sharp as a tack. I hope you have enjoyed this one soldiers incredible story, I would love to see it made into a book or a movie one day.

RIP Allan and Marie.

Alan passed away on July 8 2012, although this video is American it also applies to Allan & other brave soldiers.

This video is unrelated to Allan’s story, except for the fact it shows the courage of other brave soldiers as they face an amazing Japanese Kamikaze attack.

I realise this video depicts a different part of the world than where Allan fought, however in my opinion it is a great marching tune and always reminds me of the many brave men to who we owe so much.

Another great Australian song about the suffering & futility of war.

Thanks for visiting my One soldier’s incredible story photo blog.

Everything you wanted to know about Bangkok but were afraid to ask. 🙂

Counter only started June 16 2020.